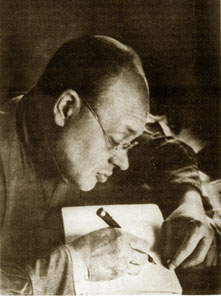

I am writing a book about a Russian Jewish writer, Isaac Babel, who thought that art could serve as the solid inner core of one’s identity, that the power of art is sufficient to redeem violence, revolution, and all possible human transgressions against morality, faith, loyalty, and plain human empathy.

This attitude was rather typical for the generation of avant-garde artists to which he belonged, men and women who had gained renown as poets, writers, painters before the 1917 Revolution but whose career matured in the Soviet era. Although in a less extreme form, intellectuals both in Russia and the West, myself included, carry the vestiges of this attitude or, rather, faith.

My self-imposed biographer’s immersion in this mind-set made it all the more interesting for me to see, if only for the late-night relaxation, the latest HBO mini-series, “Mildred Pierce,” a high-class soap about an American woman in the 1930’s Los Angeles, modeled to a degree on the 1945 eponymous film with Joan Crawford in the lead role. Although it uses the trappings of the Great Depression America, Director Todd Haynes’ “Mildred Pierce” tells us a story about the American dream as it tumbled down from the summit irrational exuberance to its low in the Great Recession, walking-wounded, self-medicating U.S.A. of our own day.

My self-imposed biographer’s immersion in this mind-set made it all the more interesting for me to see, if only for the late-night relaxation, the latest HBO mini-series, “Mildred Pierce,” a high-class soap about an American woman in the 1930’s Los Angeles, modeled to a degree on the 1945 eponymous film with Joan Crawford in the lead role. Although it uses the trappings of the Great Depression America, Director Todd Haynes’ “Mildred Pierce” tells us a story about the American dream as it tumbled down from the summit irrational exuberance to its low in the Great Recession, walking-wounded, self-medicating U.S.A. of our own day.

Played by Kate Winslet, Mildred is a strong woman from Glendale and a “straight shooter” in all matters, except two things that thicken the plot: her guilt-ridden relationship with her daughter and her occasional indulgence in good sex, per HBO conventions, with Monty, a playboy character of Guy Pearce. After her double-timing husband of eleven years walks out on her, this suburban housewife picks up the pieces and eventually succeeds by turning her home-spun passion for pies into a lucrative chain of pie shops and restaurants.

Played by Kate Winslet, Mildred is a strong woman from Glendale and a “straight shooter” in all matters, except two things that thicken the plot: her guilt-ridden relationship with her daughter and her occasional indulgence in good sex, per HBO conventions, with Monty, a playboy character of Guy Pearce. After her double-timing husband of eleven years walks out on her, this suburban housewife picks up the pieces and eventually succeeds by turning her home-spun passion for pies into a lucrative chain of pie shops and restaurants.

This attitude was rather typical for the generation of avant-garde artists to which he belonged, men and women who had gained renown as poets, writers, painters before the 1917 Revolution but whose career matured in the Soviet era. Although in a less extreme form, intellectuals both in Russia and the West, myself included, carry the vestiges of this attitude or, rather, faith.

My self-imposed biographer’s immersion in this mind-set made it all the more interesting for me to see, if only for the late-night relaxation, the latest HBO mini-series, “Mildred Pierce,” a high-class soap about an American woman in the 1930’s Los Angeles, modeled to a degree on the 1945 eponymous film with Joan Crawford in the lead role. Although it uses the trappings of the Great Depression America, Director Todd Haynes’ “Mildred Pierce” tells us a story about the American dream as it tumbled down from the summit irrational exuberance to its low in the Great Recession, walking-wounded, self-medicating U.S.A. of our own day.

My self-imposed biographer’s immersion in this mind-set made it all the more interesting for me to see, if only for the late-night relaxation, the latest HBO mini-series, “Mildred Pierce,” a high-class soap about an American woman in the 1930’s Los Angeles, modeled to a degree on the 1945 eponymous film with Joan Crawford in the lead role. Although it uses the trappings of the Great Depression America, Director Todd Haynes’ “Mildred Pierce” tells us a story about the American dream as it tumbled down from the summit irrational exuberance to its low in the Great Recession, walking-wounded, self-medicating U.S.A. of our own day.In the soap opera tradition, things get really bad, then they get really good only to get really-really bad before a reversal so spectacular that it could only be followed by an all-out crash which, in deference to the conventions of a melodrama, touched by a refreshing brush of the noir, leads to a partial and not entirely satisfactory rescue.

Melodramas are a bourgeois genre, one that arose at the time when the bourgeoisie was vying for supremacy with the aristocracy. The secret of success of those who belonged to this rising class lay in their ability to take advantage of a chance opportunity offered the dynamic society and economy of their time, and melodrama, the TV series of its time, was meant to teach a moral lesson. Melodramas are different from tragedies in that they promise a good life if the characters mend their ways – something that tragedies, and their cinematic noir equivalents do not. To give an example, “Law and Order,” a deeply noir TV series, begin with a wolf’s howl and ends its story on a note of a howling poetic injustice, as in a tragedy, with the final shot of a black screen with the two monosyllables of the series producer’s name, Dick Wolf. Subliminally they rhyme with the archetypal monosyllabic coupling of “fuck you,” each word pronounced emphatically, a condensed and effective diagnosis of the human condition seen through a tragic or film noir prism.

The first such message is that good – beach-house throw-all-caution-to-the-wind – sex and sex and sex is not only overrated but is well-nigh lethal, especially, for a mother of a small girl. While Mildred is enjoying herself with Monty, her younger daughter is suddenly hospitalized with pneumonia and dies soon after her sexually sated mom arrives at the hospital. Good sex, including cunnilingus performed by Monty later on as the two resume their relationship, is also bad for business as it clouds Mildred’s judgment condemning her eventually to a financial and emotional doom.

The second moral message should give pause to the ambitious middle-class parents who instill in their children a desire to transcend the boundary of their class. Herself upwardly mobile off-spring of a garage mechanic, Mildred programs her daughter – with music lessons, concerts, inspirational tunes, and constant subliminal messaging – to aspire to an upper-class status. The result is a young woman who has no respect for the ingenuity and effort her mother invested in the well-being of her family and utter contempt for the middle-class virtues of modesty, chastity, thrift, work ethic, and the like.

Finally, saving best for last, the series deals a shattering blow to the middle-class faith in the redemptive power of art. Vida Pierce, Mildred’s wayward and estranged daughter, is suddenly discovered to possess the rare gift of a coloratura soprano and without, it seems, much effort makes a spectacular singing career (there is no hint of this story line in the 1945 film). Vida’s coach and conductor, an Italian maestro from the old world, tries to disabuse the naïve American Mildred of her belief that Vida’s great artistry has redeemed her daughter’s meanness and would make it possible for them to reconcile. As the maestro puts it in his Hollywood Italian accent, Vida is an attractively colored “poisonous snake,” a creature to be admired as an exhibit in a zoo but under no circumstances to be taken home.

Alas, this old-world, European wisdom, falls on deaf ears (as it did in Europe among those who could not believe that the heirs to Goethe and Beethoven would preside over mass exterminations). A reconciliation between mother and daughter follows soon thereafter. It crests in the LA Philharmonic, all gold, brocade and red velvet, the bourgeois equivalent of a royal court, that the bourgeoisie so much dreams about. Gilding the lily, Vida delivers a performance of a lifetime, including singing her mother’s lullaby as an encore. Mildred is smitten and proceeds to take the poisonous snake home.

Now Mildred is set up to lose it all, and she proceeds to do so with dispatch. Soon after her investors confront her and threatened with bankruptcy unless she recovers the corporate money she had showered on Vida. She rushes to her home, no longer in the prosaic Glendale but in the high-flying Pasadena of her new husband Monty, and discovers Vida, yes, in Monty’s bed.

Melodramas cannot end on a tragic note, and in the final segment Mildred picks up the pieces again, not all of them by a long shot, but enough to stand on her feet, remarry her first husband, and yet again send her daughter packing. The last frame shows her and her husband, disenchanted at last, self-medicating their pain with hard drink.

That love, even mother’s love, not to mention sex, turns out to be a dangerous illusion and a trap is a melodramatic message even older than Jane Austen. But to be using the same brush to tar both the aspirations for upward mobility and high art turns a new page in the annals of bourgeois drama. The director Michael Curtiz, it seems, tells his viewers to forget about upward mobility and not worry much about the lack of support for the arts as they do not contribute to the moral betterment of society, perhaps, even lead to the opposite result.

He is right, of course, in decoupling beauty from truth and justice but I would rather stay with Isaac Babel and be wrong than be right in Director Curtiz’s conventional middle-class Glendale box without even an illusion of an exit, except through the neck of a liquor bottle.

No comments:

Post a Comment